Good Morning Class,

Hope you enjoy this free edition of YOUR FAVORITE PROF. If you love the content in this newsletter, consider becoming a subscriber for even more sizzling hot takes on all things fast food and even more things good teaching. Today, in anticipation of the President’s Day holiday, I’ll offer up a little bit on U.S. presidents and their relationship to fast food, and how I teach about University of Virginia booster Thomas Jefferson, Sally Hemings and presidential history.

Like many children of the 1980s and 1990s, I watched TV all the time…like all the time. I don’t know if there was concern about screen time back them (people were very concerned about music lyrics and video games, for sure, for their content—we see you Second Lady Tipper Gore), but in our house, TV time was plentiful. As long as my homework was done and I kept my room pretty clean, I could enjoy hours of sitcoms, one-hour dramas featuring talking cars and wealthy families in Colorado, and the most terrifying local news segments of all time. On weekends, my mom, my sister, and I would stay up and watch “Saturday Night Live. Even after comedic great Eddie Murphy left the show, we would rent “Best of” compilations on VHS (young people, ask your nearest elder) featuring his best skits—from the politically savvy Mr. Robinson’s neighborhood to the cable TV-skewering series about the assassination of Little Rascals character Buckwheat.

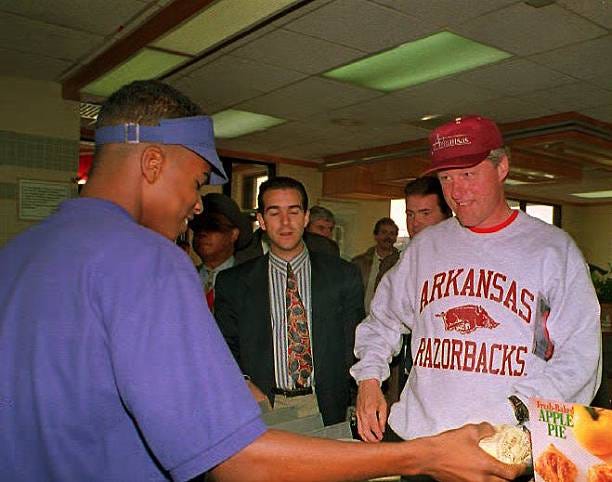

The SNL of my childhood did political humor brilliantly. In the 1990s, the late comedian Phil Hartman really delivered in his portrayal of candidate, then-President Bill Clinton. The most memorable segment was this one from 1992, in which President Clinton talks to constituents at McDonald’s.

Before the election of Donald Trump, few presidents had been as linked to fast food as Bill Clinton. Clinton’s association with fast-food was part of a larger set of critiques/observations of the candidate in 1992. In news reports, Clinton was often portrayed as a charismatic, yet unrefined. In a form of bias that still lingers today, Clinton’s status as a Southerner made him a target of jokes about his intellect. Despite his incredible academic achievement and ambition, Clinton was also perceived as relatable in his low-brow tastes. Clinton’s proximity to fast food is fascinating to me, and I attribute a 1998 Toni Morrison piece “On the First Black President,” from The New Yorker as particularly illuminating when I think about the layers embedded in the scene of Hartman’s Clinton sampling fries and McRib sandwiches while talking about community development banks. The Nobel laureate offered a comment for the magazine’s “Talk of the Town” section about her decision to take a break from the endless news cycle that covered Clinton’s impeachment proceedings for his perjury, obstruction of justice, and abuse of power charges (which is captured smartly in Slate’s Season 2 of the Slow Burn podcast). Morrison argued that Clinton was the nation’s “first black President,” an often-misunderstood idea about the 42nd president, which would reemerge during the campaign and election of the first actual black president in 2008. Although people often rehash the remark to suggest that Obama’s blackness was an issue up for question and debate, Morrison’s reflection is illustrative in that she enumerated Clinton’s blackness by pointing to the way he was being relentlessly pursued by Congress, which she said mirrored the racial biases of the criminal justice system. Morrison asserted that it made sense that Clinton was the target of a witch hunt, because:

“After all, Clinton displays almost every trope of blackness: single-parent household, born poor, working-class, saxophone-playing, McDonald’s-and-junk-food-loving boy from Arkansas.”

Clinton’s famous consumption of Egg McMuffins and Big Macs while on the 1992 campaign trail may have been an outgrowth of a grueling campaign schedule and the fact that as a Baby Boomer; he grew up with the brand and he developed a taste for it (he’s now mostly adhering to a vegan diet—BTW). Regardless of the origins of Clinton’s love of McDonald’s, the ‘racial’ implications of Clinton’s taste for fast food, and Morrison’s including fast food as a marker of blackness inspired me to write my book FRANCHISE, which examines how McDonald’s become black, and why fast food is consumed by people all over the world, but it means different things in different places.

For Clinton, his presence at McDonald’s placed him in that sweet spot of relatable and in-touch with the everyday American person. Voters saw him as the antithesis to the patrician George H.W. Bush (the dad) or the Greatest Generation candidate Bob Dole, who ran against Clinton in 1996. The message was clear: Regular people eat fast food and it was time a regular person was in the White House (regular meaning attended Georgetown University, Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship, Yale Law School, and elected the second youngest governor in your state’s history). Although Clinton’s love of fast food was trolled the most, the White House has been a friend of the fast food industry for decades. Richard Nixon offered generous subsidies to fast food chains like All-Pro Chicken, a Black-owned business that he often pointed to in order to prove his commitment to Black economic power. The Obamas enjoyed elevated fast food like fast casual greats Five Guys and Shake Shack. And Donald Trump’s made the perplexing decision to serve the 2018 National Champion Clemson Tigers football team an assortment of cold fast food items (because that is exactly what you crave when you want to celebrate a major achievement and attending an event that requires boarding an airplane). If you want to learn more about presidents and their penchant for fast food and their entanglements with the fast food industry, check out historian Chin Jou’s excellent piece in The Washington Post, “Donald Trump isn’t the first president to give fast food his seal of approval.” I’m deeply indebted to Jou’s book Supersizing Urban America: How Inner Cities Got Fast Food with Government Help and her research on the fast food industry’s ability to lobby for legislation to protect it from raising wages, impact on health disparities, and its influence on nutritional guidelines.

Suit up in your favorite running shorts and do some reading and listening over this long weekend about the politics of the American palate.

Last week, I opened up class with a brief acknowledgment of the Super Bowl. I like to open up the week with a news hook, and I want my students to think about the backstory and implications of notable events. As students were joining the Zoom call, I screened this clip of Kim Weston’s performance of The Black National Anthem from 1972 and asked them to consider why they think the NFL decided to include it in the Super Bowl. And, after everyone was settled in to our virtual classroom, I showed a clip from the National Congress of American Indians on racist sports mascots and the harm they do. I find this approach is more substantive than simply asking, “Who did you root for?” or “What was your favorite commercial?”

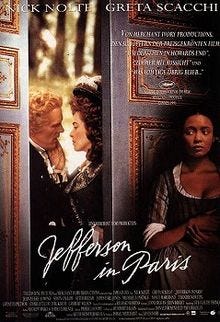

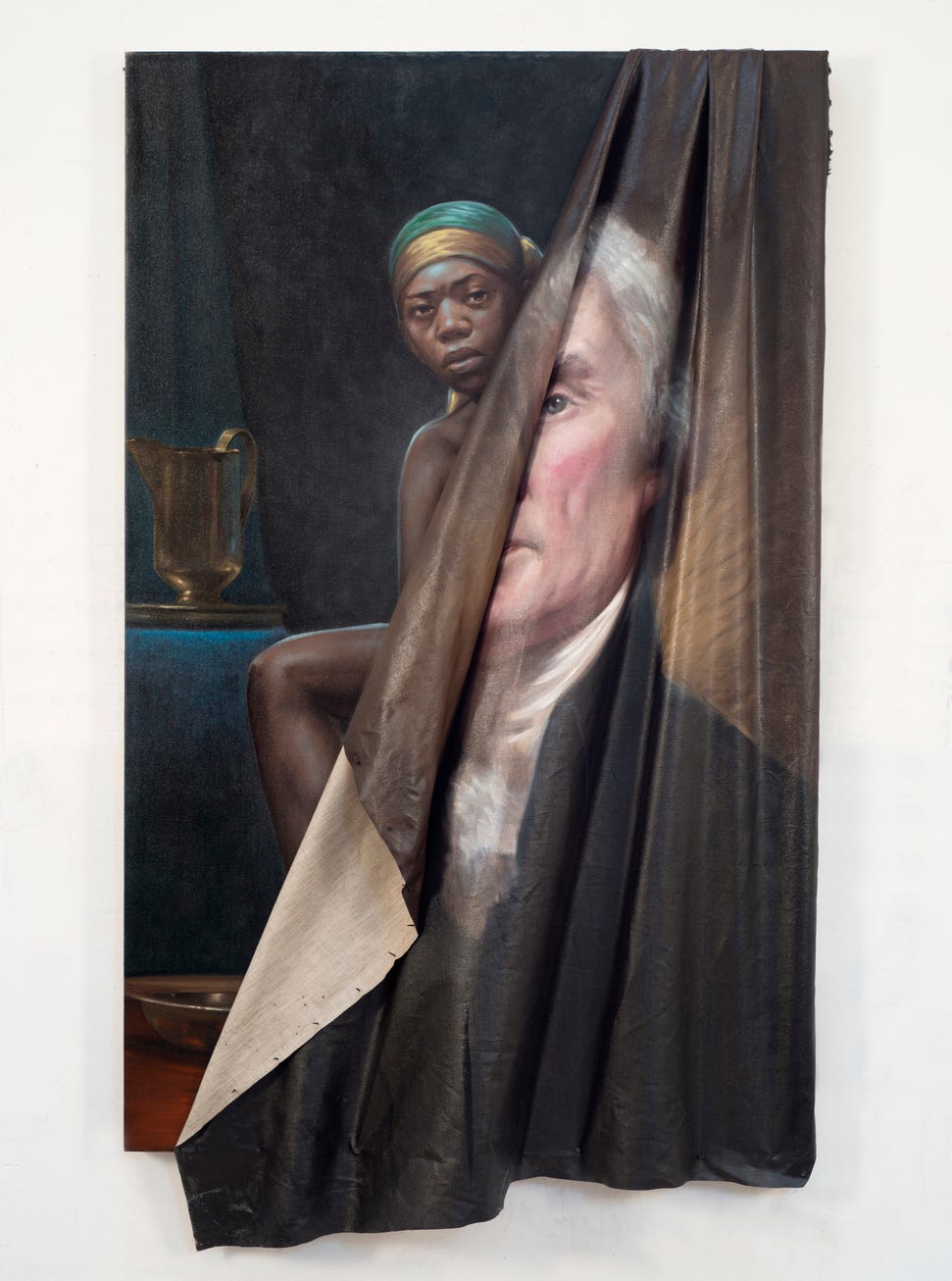

Due to COVID-19 and shifts in the academic calendar, I’ll be teaching on President’s Day. I rarely teach classes that focus entirely on presidents, but they loom large among my favorite teaching topics, including the history of the civil rights movement and my black capitalism class. In the fall of 2018, I taught a seminar entitled “Race and Racism in the White House,” which examined presidents and policies from Washington to Trump. The syllabus included Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s book Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge and Annette Gordon Reed’s Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. By centering slaveholding as ‘presidential’, I guide students through various discussions about how presidents are memorialized and the appeal of ‘founding father’ or ‘great leader’ myths that erase slavery from the narrative arc of the pathways to the White House—military service, diplomacy, agriculture, or industry.

This past week I lectured on Thomas Jefferson and slaveholding in my “Sex, Love, and Race in American Life and Culture” class for a discussion of Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. I pair Jacobs’s, searing account of her sexual exploitation while enslaved with a clip from Ken Burns’s 1997 documentary “Thomas Jefferson,” in which a group of historians ‘debate’ whether Jefferson fathered children mothered by Sally Hemings (this does not age well). Most of my students have heard something about Hemings and I always emphasize that in Jefferson’s time people discussed his fathering of the children (so this isn’t a case of cancel culture [sigh, it’s not a real thing] or historical revisionism) AND I ask them why do they think the talking heads in the series take up this issue so passionately (the words “inconsistent with everything we know about Thomas Jefferson” are uttered and his granddaughter’s reaction that this was a “moral impossibility” is also offered). Why must Jefferson be ‘innocent’ in order to be studied? Why does the United States have to be innocent?

I finished the lecture with a examples of other stories that have emerged about presidents and political leaders that use the idea of a Black child as a source of scandal, including the famous South Carolina robocall that insinuated that presidential hopeful John McCain fathered a Black child (he did not; he adopted a child from Bangladesh), as well as tabloid accounts of Bill Clinton’s secret Black son that were revived when Hilary Clinton ran for president (call back to the beginning of this newsletter). Then, I ended the class with and ad from short-lived presidential hopeful Bill de Blasio’s mayoral campaign, in which his Black son Dante was prominently featured. I wanted them to note continuity and change over time not only in racial representation in political discourse, but the political ‘uses’ of family and messaging.

As a number of us do Zoom school, I implore you to use clips to open and close class times to give students a change in visual stimuli, whether you are the only thing they see on their screens or if you use slides. The shift is great, and I like to use yout.com to do my clips, embed them right in the slides to reduce the headache that comes from toggling between slide presentations and internet browsers. Most classes have unfinished business at the end—questions that go unanswered or areas of analysis that can’t be addressed—I like using Canvas (or whatever online teaching portal you use) to post what I call “Pop Culture Extras,” to encourage students to keep thinking about what we have explored in class. For the Jefferson class, I link to a C-SPAN discussion about the Hemings family at Monticello, documentaries on dirty tricks and political campaigns, and articles about the representation of slavery at National Park Sites, among other important sites. I’ve recently added this excellent summation of the controversy about White-House adjacent/Broadway muse, Alexander Hamilton and a scholar’s work on his ties to slaveholding and the ways that made one presidential historian (I’m looking at you Ron Chernow) really grumpy.

Hope you have a safe, President’s Day weekend. You can catch yours truly among the many talking heads in the documentary about the Reconstruction-era President, Ulysses S. Grant. May the mattress sales be abundant and the specials on cherry pie fruitful (and if you want a great corrective to all things George Washington, check out Alexis Coe’s You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington).

Your Favorite Prof