Labor Daze, Part II

And, Less Reading, More Being

Friends, many of you are celebrating the end of a school year—as educators, parents, supportive observers—and there are many reasons to believe that this moment will be the last gasp of Zoom School. Although we can’t quite fully exhale yet, in the meantime, there is lots of learning about fast food and teaching to keep us busy. If you don’t want to miss the opportunity to take this weekly class with YOUR FAVORITE PROF, subscribe today.

Last week, I delved into the reasons why the idea that nobody wants to work right now is inaccurate, and why the myth of a labor shortage is being used as a weapon to clip federal benefits to struggling people. Adam Chandler, fellow fast food scholar, wrote about this for The Washington Post. The labor crisis is the figment of the nefarious imaginations of service industry leaders who can’t believe that workers don’t want jobs that are harmful and pay too little for survival. This talking point also deflects attention from the important scrutiny that continues to question the quality of jobs, the unaddressed harassment, and the especially low wages in the fast food sector. Chandler sums it up beautifully:

This is why when we talk about the recovery and the return of the low-wage workers who were disproportionately affected by pandemic unemployment, we should be looking at the jobs on offer and not the people. Before the pandemic, the state of hourly work was fossilized by a federal minimum wage standard that hasn’t budged in more than a decade along with real wages that haven’t moved in over 40 years. Instead of supporting comprehensive benefits, lawmakers in some states introduced ostensibly progressive initiatives such as predictive scheduling, which ensured that some hourly workers could, at least, know their work schedule more than a few hours ahead of time so they could plan their lives and secure child care. In the shadow of an unparalleled public health crisis, the default factory settings for American workers seem even more absurd. And yet, these conditions have only changed in a few cases since the pandemic began and, in many instances, have only gotten worse.

As this myth has been debunked by a number of economists, think tankers, and journalists, workers have continued to articulate the fundamental problems of fast food labor. On May 19, workers across sectors—trucking, gig economy, apparel manufacturing, and food processing—participated in one-day strikes to raise awareness about low pay, hazardous working conditions, and suppression of worker organizing.

In the fast food world, McDonald’s workers in cities from Orlando to Los Angeles —mostly organized by Fight for $15—walked off the job in the service of the movement’s two demands: A labor union and $15 an hour. As I wrote last week, $15 an hour is a modest wage in most parts of the country, but some argue that it’s a solid start considering that $15 is a little over double the current wage of $7.25. As Sarah Jaffe wrote in The American Prospect on May 19, one Fight for $15 worker, who was recently offered a $14 an hour position at McDonald’s, is far from enjoying financial security after years of making poverty wages:

Precious Cole first went on strike when one of her co-workers at Freddy’s Frozen Custard & Steakburgers in Durham, North Carolina, contracted COVID. She and her co-workers, she said, were told they had to quarantine for two weeks, unpaid, or provide proof of a negative test.

Cole is 34 and has spent many years in food service, at one point working full-time while homeless, unable to afford shelter. She’s now living with her mother, who was recently hospitalized with a blood clot in her lungs and cannot work due to her health.

“It’s a start,” Cole said. “We’re gonna stand in solidarity, we want the $15. We want a union, so that stuff like this can’t happen and that we have a voice. This is us letting them know, ‘We’re here to stay and we’re going to be in your face. Every time you turn around, we will be there.’”

Cole’s story reminds me of the devastating experience of McDonald’s worker Cristian Cardona, the subject of Eleni Schirmer’s New Yorker article about the Fight for $15 in Orlando, Florida. A car accident—one of the many kinds of unexpected events that can derail a poor person for months, if not years—upended Cardona’s life.

Cardona, who is twenty-one, has been working at McDonald’s since 2017. He currently makes eleven dollars and thirty cents per hour. He lives with his parents and younger sister, in Orlando. His mother works as a cleaner for a bank. His father worked as a hotel-shuttle driver, but when the pandemic decimated tourist industries he lost his job; he has since found work doing construction and odd jobs. Cardona’s parents each make less than twelve dollars per hour.

Many of the workers featured in these investigative pieces about fast food workers are Black or Latinx, and the majority of them are women. The perception that workers are lazy or are willing to abuse the largesse of a benevolent federal government is magnified when the workers in questions are not White. The punitive, state-level responses to workers’ hesitancy or resistance to rejoining the fast food workforce not only reflects a conservative approach to state assistance, but it is also fuels racist and sexist ideas about the value of labor. As Jaffe notes:

Workers in the service industry and on unemployment tend to be Black and Latino. Fifty percent of South Carolina’s UI recipients are Black, rising to a whopping 66 percent in Mississippi…Food service work is at once women-dominated and low-paid.

So, what is a thoughtful consumer to do?

This one is a tough one. Voting with your feet and stomach, or all-out boycott, can feel like it punishes the people most dependent on revenues to keep their jobs. Also, unorganized boycotts can fail to deliver when there aren’t clear goals about which levers need to be pulled or just dismantled. As a historian of the civil rights movement, I try to emphasize to students how much skill and planning went into boycotts of the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. In the digital age, it’s easy to believe that with more channels of communication available to us that boycotts only need some messaging and an ask. This piece by Zephyr Teachout offers some insights into the dilemma of boycotts, and why corporate structures are harder to punch in the gut. Yet, the strategy is still worthy of our praise. I appreciate the unsexy and very bureaucratic way that Jo Ann Gibson Robinson describes the mechanism that made the Montgomery Bus Boycott possible in this sliver of history, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women who Started it: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson. It’s one of the most descriptive explanations of how the sausage was made at mid-century: She explains how she and her friends, including the seasoned activist Rosa Parks, got access to mimeograph machines and paper, and she includes things like how you ensure boycotting people had hardy shoes to sustain them during 381 of public transportation abstinence. Robinson once said:

“That boycott was not supported by a few people; it was supported by 52,000 people."

Fifty-two thousand is the number of leaflets that the city’s Women’s Political Council made to circulate the announcement that a boycott was being mounted.

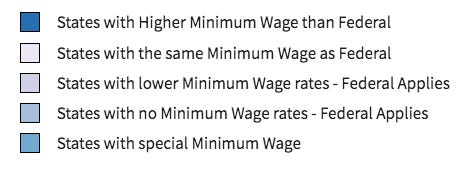

As someone who is a more than a little skeptical of conscious consumerism, I think your best bet for supporting fast food workers is to support policies that work for all workers. Support candidates that run on a platform that calls for raising local and state wages. If you are not an hourly worker, do you know where your state stands on the issue? Take a look at this info graphic from the Department of Labor and read this summary to learn about what people are being paid where you live.

Finally, support campaigns and organizations that are confronting the systemic problems that allows for employers to exploit workers. I’m a big fan of the reignited Poor People’s Campaign, which is co-chaired by Rev. William Barber. Barber has effectively presented the interlocking issues of racial and economic justice in a framework that calls upon the nation to engage in a ‘moral revival.’ If you haven’t had an opportunity to hear Rev. Barber layout the argument for this shift, head over to YouTube and check him out. You wont’ be sorry.

To all the educators who are approaching or have crossed that finish line, congratulations! If you are looking for suggestions for summer reading to be a better teacher (or be less racist, or be more organized)—I can’t help you with that! Actually, I have read and seen tons of books promising to help us all do these things, but after a year plus of pandemic teaching, let’s rethink the impulse to use summers for self-improvement a little differently. Instead of assigning ‘teacher homework’ to the educators I have been working with this year, I’ve been asking them to focus their energies on what they want to become. It’s a simple exercise, but it can possibly unlock a deeper understanding of yourself and the work you do. Fill in the blanks:

I want to be a better teacher in my classroom, so the places in my life in which I can build my confidence are…

I want to be a better teacher, so the way I can engage more with people from an empathetic place is…

I want to be a better teacher, so I can do the following things to manage my anxiety…

Who we are in the classroom is often a reflection of who we are in the outside world—for good or for bad. Trust me, when we address the personality traits and character flaws that make our out-of-school lives challenging, we find our students more responsive and we are able to engage more deeply with the relationships in front of us. Over the following summer, I will continue to offer a few insights into how we can reduce some of the barriers to good teaching.

We made it!

YOUR FAVORITE PROF

I like this:

"...when we address the personality traits and character flaws that make our out-of-school lives challenging, we find our students more responsive and we are able to engage more deeply with the relationships in front of us."

I'll steal a line from business advice I once received:

"You don't have teaching problems. You have personal problems that reflect on your teaching practice."